Mount Shasta Volcano

The record of eruptions over the last 10,000 years suggests that, on average, at least one eruption occurs every 800 to 600 years at Mt Shasta. Future eruptions like those of the last 10,000 years will probably produce deposits of ash, lava flows, domes, and pyroclastic flows, and could endanger infrastructure that lie within several tens of kilometers of the volcano.

Lava flows and pyroclastic flows may affect low areas within about 15-20 km (9 to 13 mi) of the summit of Mount Shasta or any satellite vent that might become active. Lahars could affect valley floors and other low areas as much as several tens of kilometers from Mount Shasta.Owing to great relief and steep slopes, a portion of the volcano could also fail catastrophically and generate a very large debris avalanche and lahar. Such events could affect any sector around the volcano and could reach more than 50 km (30 mi) from the summit. Explosive lateral blasts, like the May 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens, could also occur as a result of renewed eruptive activity, or they could be associated with a large debris avalanche; such events could affect broad sectors to a distance of more than 30 km (20 mi) from the volcano.

On the basis of its behavior in the past 10,000 years, Mount Shasta is not likely to erupt large volumes of pumiceous ash in the near future. The distribution of tephra and prevailing wind directions suggest that areas most likely to be affected by tephra are mainly east and within about 50 km (30 mi) of the summit of the volcano.It has been suggested that because it is a long-lived volcanic center and has erupted only relatively small volumes of magma for several thousand years, Mount Shasta is the most likely Cascade Range volcano to produce an explosive eruption of very large volume. Such an event could produce tephra deposits as extensive and as thick as the Mazama ash and pyroclastic flows that could reach more than 50 km (30 mi) from the vent. The annual probability for such a large event may be no greater than 10-5, but it is finite.

|

|

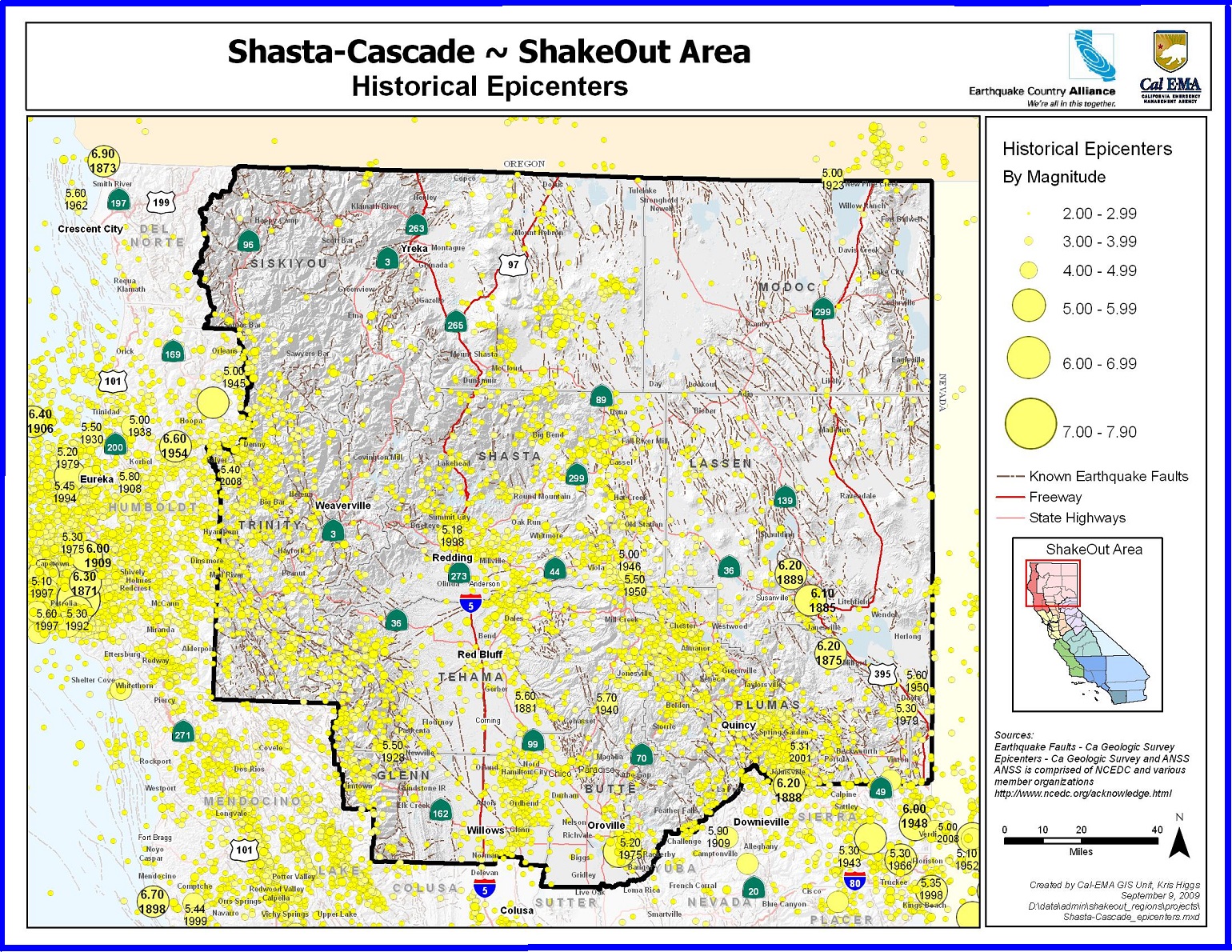

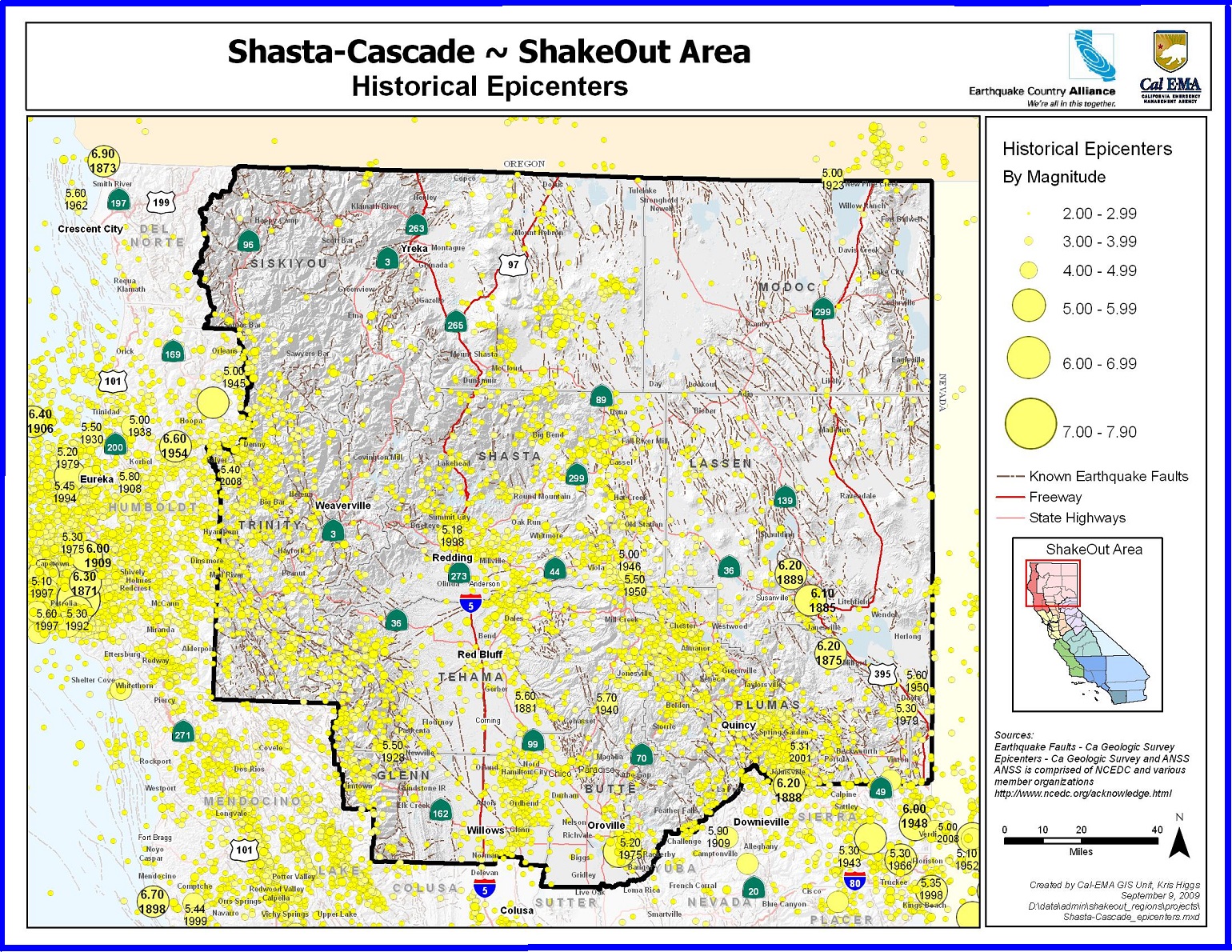

SHASTA CASCADE EARTHQUAKE HAZARDS

Those who are lucky enough to live in the northernmost part of the state enjoy spectacular scenery and remote vistas. The Trinity Mountains, Modoc Plateau, Shasta and Lassen peaks show how the forces that created them are still shaping the landscape today. But no matter where you live in the Northern and Northeastern parts of the state, you live in earthquake country. Understanding the risks and preparing to survive and recover can help keep you and your family safe. The Shasta Cascade area may seem remote from the well-known faults in the state such as the San Andreas. It may be a surprise that almost everyone in the region lives within 20 miles of an active fault. The Modoc plateau is a region of both active volcanism and faulting and much of the northeastern part of the state is being stretched apart by basin and range faults. Residents could also be affected by very large earthquakes further away and closer to the coast. It doesn’t take much shaking to trigger landslides that can quickly block roads and highways, isolating the region.

|

|

Lassen Volcanic National Park

All four types of volcanoes found in the entire world are represented in Lassen Volcanic National Park— shield (Prospect Peak), plug dome (Lassen Peak), Cinder Cone (Cinder Cone), and Composite (Brokeoff Volcano) volcanoes.In August of 1916, Lassen Volcanic National Park was established. The park and Lassen Peak take their name from Peter Lassen, one of the first white settlers in the northern Sacramento Valley, who discovered of a route through the mountains called the Lassen Trail.

To see these volcanic sites, Lassen Volcanic National Park offers both summer and winter weather activities. With over 150 miles of hiking trails, both day hiking and backpacking are popular summer activities. Winter conditions often begin as early as October and persist through June or July making snow play, snowshoeing, and backcountry skiing great options for cold months.

|

|